Some Definitions

Some Definitions

A spec script is a screenplay that’s written “on speculation.” That is, you, the screenwriter, write the script without any development contract or promise of payment in place, in the hopes of getting it optioned, sold, or gaining representation by an agent. It’s how most screenwriters break into the industry.

But the spec script will undergo many changes between the time it’s first optioned or sold, and the time shooting begins for the movie. That leads us to…

A shooting script — a script that has been vetted, changed, rewritten and is now being used as the blueprint for filming the movie. It’s a different animal than the original spec, in a few fundamental ways.

It’s important to know the difference

Often times screenwriters pick up bad habits from reading shooting scripts available online.

It’s therefore very important, if you’re a new screenwriter submitting a spec script for review, that you understand the differences between the two formats.

Five Key Differences Between Spec and Shooting Scripts

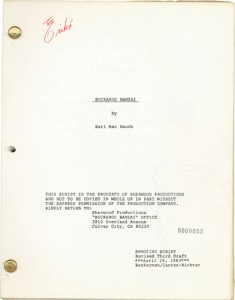

1. The Title Page

A spec script should have the title of the movie, “written by,” the author or author’s names, and some contact information (for author or agent). WGA notification is optional.

A shooting script may have, in addition to the above, multiple subsequent writers, studio or producer contact information, draft or revision dates, and copyright notices. So stay away from these things in your spec.

If you don’t know how to correctly format your title page (or script), or even if you think you do, I highly recommend this book:

The Hollywood Standard: The Complete and Authoritative Guide to Script Format and Style by Christopher Riley

You never get a second chance to make a first impression.

2. Scene Numbers

Spec scripts should not have scene numbers.

So if you’re using them as some sort of cool tool to gauge the length of your script, while writing it, make sure you remove them before submitting your script to anyone.

3. Title Sequences

Spec scripts should avoid any reference to opening credits or title sequences. Screenwriters should just focus on crafting the best opening scene they can. Even if you think your concept for opening titles is wicked brilliant, it may brand you as an amateur if you incorporate such a sequence into your spec1.

Shooting scripts can contain title sequences (or at least reference their location) because at that point, the script is finalized and typically the Director knows how everything is going to play out. The guys that look after the title sequences for films are masters of their craft. They won’t be left floundering if you don’t “leave a spot” for the opening titles in your screenplay.

4. Camera Direction

In spec scripts it’s never a good idea to include camera directions (PAN, DOLLY, TILT UP, ZOOM IN ON, CRANE UP, etc.). It’s the Director’s job to interpret your screenplay and come up with their own shots.

It is okay, however, to craft a scene that implies the camera direction — that directs the mind’s-eye of the reader. Just don’t specify a camera shot in your spec, unless it’s absolutely integral to your vision and pivotal to your movie.

Example:

CAMERA TRACKS Bella as she plummets toward the raging ocean.

Instead, write:

Bella plummets toward the raging ocean.

The Director will get it, without your telling him how to film it.

5. The Writing Craft

Often times the shooting script will not be as well written as the spec script. The very nature of breaking scenes up into specific shots can often compromise the writing quality of the original script. Having already been sold on the movie’s merits, scenes may be written, or rewritten for functionality over form, speed over eloquence. Typos may even sneak in.

But that doesn’t mean that the original spec script wasn’t a flawless work of art. It’s not okay to point to errors or poor writing in shooting scripts and say, “Well, if they did that in their script, I can do it in mine.” No can’t. You still have to sell your screenplay.

Also keep in mind that Screenwriter/Directors sometimes write screenplays for themselves. In these cases they tend to include more camera direction and different language — even in “spec scripts” — than they would normally have used.

Bottom Line

Always make your spec script the best it can be. Thank goodness we live in an age where a multitude of scripts are available to us with the click of a mouse, to learn from. Just be wary of picking up bad habits from shooting scripts.

If you can choose between versions of scripts online, take a look at the earlier versions as well. They may be truer to the original spec.

- It’s perfectly acceptable, however, to craft a scene that lends itself to opening titles — such as establishing the location and tone of your opening ↩

Excellent post..Keep them coming 🙂 Thanks for sharing.

Too many complemitns too little space, thanks!

thank you for being so clear and specific

sometimes we know these things in our heads,

but hearing a writer spell it out on the page, it lets your brain absorb the concept in a different angle different than some preconceived notion that we believed previous

Wow, excellent article

Hey donc — my pleasure. Thanks for the excellent feedback!

Hi, just wanted to mention, I loved this post.

It was practical. Keep on posting!

I appreciate the feedback, thanks!

Excellent advice, at 38 i felt it was too late to write(always wanted to,never the time), but having a 6 month old daughter in my life now, ive had many hours not getting back to sleep myself to fully explore using the internet on how to write! the differences you have explained has been a revelation to how i want to write ,thank you so much!

Hey Robb, so glad the post was helpful to you. Thanks for letting me know!

Great info post. Spec writers can never have too much good advice. I do have a question…when just two characters, a male and female are introduced by name in scene opening, how often can (or should) they be referred to throughout the scene as pronouns “she and he”?

Thanks

Hi Dyana, there are no hard and fast rules for the number of times you can use pronouns for the character names. You basically use the character name the first time in a scene, to identify them, then you use “he” or “she” as the case may be, until you either need to remind the audience who the “he” or “she” is, or it gets too repetitive to use “he” or “she,” or you need to use the character name to avoid confusion (like if another woman enters the scene). Hope that helps.

Wow! I’ve been researching “do’s and don’ts” because I wasn’t happy with the feedback I was getting. I’m learning from the ground up and had been told that actually reading screenplays was the best way to learn. Nuh-unh!! I was getting raped on my feedback saying “this isn’t clear… that isn’t clear… your execution failed because you failed the basics”. So, I recently went back to the drawing board and couldn’t figure out what I was doing wrong. All my actions were present-tense, format flawless, felt like I kept the story moving, so on and so forth. So, I started over, wrote it more “bookish” to see what I could take away. Working backward instead of forward. And then, something stood out to me that I had forgotten. Shooting script versus Spec script. I had been working from scripts that were shooting scripts, that’s why none of my stuff made sense to me but even as I read those, they made sense to me. It’s because they were for the finished product of something I’ve already seen. So, I know what to correlate it to and how to interpret it. It didn’t dawn on me that what I was writing was meant to be read as a “I need to feel your visuals” as opposed to “I need to see visuals”. I even got into a ranting argument with someone who reviewed a script about it. It’s because of rule number 5 that I very recently came to understand what was completely expected of me. I was writing incomplete sentences because it was what I had seen all the scripts do. I completely went for functionality over form because I had thought THAT functionality was a form. It obliterated my writing quality to the point I was considering simply selling loglines (which I feel I have a bunch of great ones) because my feedback wasn’t bad but was never satisfactory to any one. I’d say that number 5 is a death trap for many aspiring writers. Reading and emulating shooting scripts nearly dashed my dreams of being something in the industry. I feel like that’s a point that should be expressed greatly to anyone wanting to write films. I’m completely glad I came across that number 5 and feel like I can rest easy as I’ve been working on rewriting to that effect.

Hi Isaac, thanks for the great feedback! There’s certainly a lot of misinformation/lack of information out there. I’m so glad my article helped you to crystallize some of the spec writing norms. All the best!